The Signal and the Sign

When a radio station with multiple lives intersected with mine.

It was a busted tape recorder that led me to a part-time data entry gig in Owings Mills, Maryland in the fall of ’96. With college graduation 7 months away, the future was a huge question mark, but I was certain of one thing. I had to keep my mixtape going.

Radio was a constant companion in my Roland Park studio apartment. By day I was filling my head with transport phenomena and reactor design, and by night, the deeper works of Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and Steely Dan. My professors at Johns Hopkins were brainacs, but when it came to real-world advice, they had few answers. The DJ’s on 103.1 WRNR might as well be sitting next to me at the bar, yet they seemed to have all the answers.

I discovered RNR in early ‘96, and quickly realized I had stumbled on a treasure trove. The Annapolis station was a latter incarnation of WHFS, an originator of freeform radio, and the subject of a wonderful new documentary, Feast Your Ears. Unlike the sanded-off edges of public radio, RNR’s hosts were understated, opinionated, and embedded in the homegrown music scene. They presented artists like Dylan I had dismissed as dusty old legends, and let me convince myself of their greatness and continued relevance.

At the same time, new discoveries came at me like a firehose. I wondered how I’d made it this far without the irreverent whimsy of Jonathan Richman. I couldn’t resist when the underworldly voice of Tom Waits grabbed ahold of me like some sonic shadow demon. RNR stood for rock n’ roll, but first and foremost, the other well-known shorthand. The station’s mission was to support us listeners as we kicked back with a smile, legal or otherwise.

RNR kept an impressively consistent sound while covering countless genres and still allowing each DJ’s personal style to come through. Between my classes I tuned in to mid-days with Damian, who introduced each song as “this piece.” Hey, no classical terminology here! But it worked, because the blues too was art, and deserving of the same pedestal.

On weekends, fellow HFS alum John Hall brought wit and wisdom that made Hall’s Bar & Grill appointment listening. Back-announcing with an “only on RNR” brag… bantering with live callers… or breaking out Cub Koda’s “Random Drug Testing”… all of it went against commercial radio decorum, and it was glorious. One August afternoon, he abruptly announced his departure for California, and I let my tape roll for his final 4 hours, a musical meditation on sad goodbyes mixed with the undeniable call of the open road. And I was there cheering when he returned a few months later.

That’s right, I was more than a listener, I was always working on a project. Making mixtapes was a year-end tradition for me since my early teens. I recorded songs off the radio all year, then compiled them in some sense of order (or disorder). Which brings me back to the panic of being suddenly recorder-less – because this year I was taking it to a new level.

With my cash flow restored and new tape recorder in hand, I was back in business. Joining musical styles or topics was instinctual, but RNR taught me I could be more ambitious. I learned the art of the segue, assembling a set of music where each song built on the last, building momentum to a climax and then a resolution, hopefully surprising along the way, and leaving the listener in a better place.

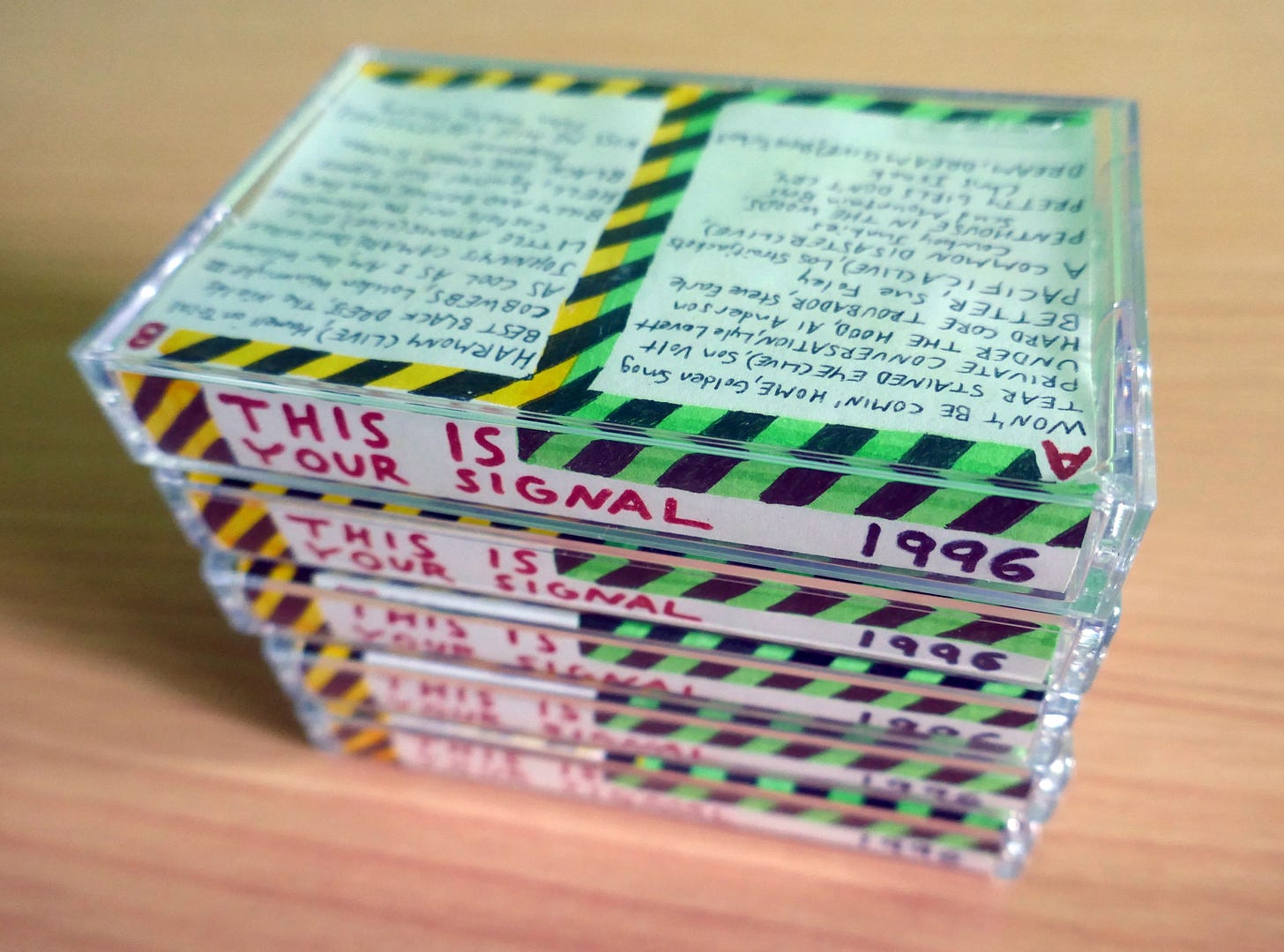

How much creative freedom can you have as a curator with ten 45-minute sides of tape to fill? A lot, it turns out. Drawing on my favorites of ’96 - the Mysteries of Life, Gillian Welch, the Subdudes, and more - I crafted sets that drew from my own experience as a college senior. Pressure. Inertia. Nightmares. Oh my. But I balanced my angst with upbeat sets designed to rock out, space out, and swing out. I never ventured to put down on paper what it felt like to be 21; I let the mixtape be my time capsule.

Outside my apartment building was a traffic light with a sign that read, “This Is Your Signal.” It always puzzled me, why would the traffic be confused? Sure, there was another intersection a short distance ahead, but it seemed unnecessarily obvious. Maybe the sign was there for something else.

Once I started listening to RNR, no other radio format would do. It was clear I had found a place I belonged, and a love for music that would accompany me wherever I went in life. No one needed to spell it out for me on a sign. Even so, I chose it as the title of my 1996 mixtape. RNR was made by others, but it was mine, and for a radio signal, it was as good as any divine intervention one might look for in the sky. So, on the nose though it was, I came to appreciate the road sign. Because it’s a worth a reminder that music can guide you in a world where guidance is often lacking.

Nearly 30 years later, I’ve never built a reactor, but I still build playlists. If the ‘90s were weird times, the future has truly gone mad. But luckily, we still have freeform radio! Give it a chance, it might get you through the rest of your life.

I’ve always loved that sign — and loved RNR. Thanks for bringing me back. That was my signal!

That’s a great memory, Matt Thank you for sharing so awesome 😎